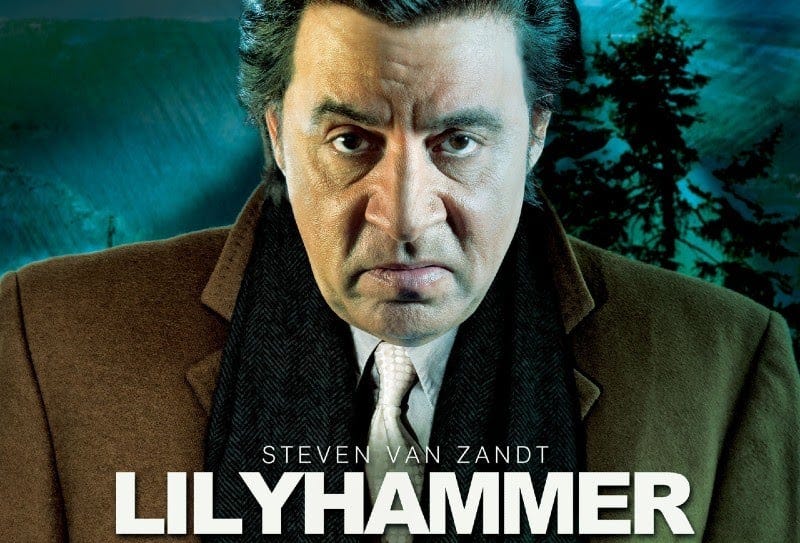

Plentiful is Doordash’s Lillyhammer. Lillyhammer, for those who don’t remember, was Netflix’s first original content show. It centered around Frank “The Fixer” Tagliano (played by Steve Van Zandt), a New York mobster who moves to Lillehammer, Norway as part of the Witness Protection Program. Plentiful is a generic bowl restaurant that magically, digitally appeared one day with locations in California, New York, Texas, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Plentiful is also Doordash’s first ‘original content restaurant’. Those quotes around ‘original content restaurant’ are working really, really hard.

The other thing about Plentiful is that it doesn’t really exist; you can’t, like, go there. It’s a ghost kitchen being produced out of any number of small, often local, restaurants who are being used as white label producers for the brand. Full disclosure, I actually received the pitch for becoming a Plentiful restaurant at one of our restaurants. The deck promised to ‘grow our business with a turnkey delivery only restaurant’ and ‘earn incremental profits and optimize underutilized resources by adopting a fully developed brand.’ It also walked through how to get up and running in 3 weeks. In week 2 it directs to read the ops guide while waiting for product. Training happens in week 2.5 and we’re off and running in week 3. The deck had a little ROI calculation and an action ready Sysco order guide.

What do Plentiful and Lillyhammer have to do with each other? In two words, vertical integration- platforms becoming producers of the content they had previously just distributed. Why are they doing this? In one word, money. Vertically integrating will allow for cost efficiencies, greater revenue opportunities, supply chain leverage, exclusive content, and greater control. At least that's the theory and it’s played out pretty well for Netflix. Spotify is doing the same thing with podcasts. Apple, Tesla, Zara are all examples of vertically integrated companies, to name a few.

What Doordash is doing is different and, I’d argue, more sinister and scary. If we extend the Netflix metaphor, what Doordash is doing would be like Netflix going to just about anyone with a cell phone camera and saying here’s a script for a movie, make it happen. Oh yeah, and then they don’t give any credit to the people who made the movie. To be fair, much of the Ghost Kitchen brand world is an awful commodification of both local business and kitchen work. Kitchen employees are tasked to make random food to drive more revenue out of their labor input. This is not a recipe for yielding quality food, just ask Mr. Beast.

Another scary element of this is the potential for Doordash to put their thumb on the algorithmic scales. If someone searches for bowls or healthy dinner, Doordash could serve up Plentiful first. Have you ever noticed how many of Netflix Top 10 tend to be Netflix productions. Doordash could subsidize with free delivery or other promotions indefinitely or make it more lucrative for drivers to accept pickups for Doordash brands over time. Also, as the restaurant is solely reliant on Doordash for orders, they have little negotiating power if/when Doordash decides to jack up the revenue share fees. Whatever leverage you can conceive of Doordash asserting, assume they will.

To be clear, I think what Doordash does is important for restaurants and they are generally good at it. I cannot imagine finding a way to do our own delivery at scale for anywhere near the cost of the revenue sharing. Removing the constraint of our physical space as a limiting factor for sales is crucial to our business. Vertically integrating at Doordash is also a good idea that could have been transformative for restaurants if it had been done in a different way. So many movies and shows are made now that never would have been in a purely linear environment. The same could potentially hold for restaurants with a more virtuous approach to integration.

Where does this go from here?

Let’s assume that other platforms will also get into the game. That means Ubereats for sure. Imagine a world where Ubereats supports the opening of restaurants in lower rent, destination neighborhoods and then leverages driver networks to get guests there and facilitate delivery. That might simultaneously lower barriers to entry and support first time entrepreneurs.

It’s also interesting to think about other platforms integral to the restaurant industry. There’s a good argument for Toast or Square to get into this space from both a vertical integration and product innovation standpoint. What about the credit card companies and processors? AMEX has taken a couple steps in the ‘producer’ direction with their Resy acquisition and numerous pop up partnerships. Similarly, Chase acquired The Infatuation bringing them closer to the ‘content’ they typically just had a transactional role with. The big food distributor and liquor companies could also move in if the regulatory environment allowed it.

The most interesting vertical integration will probably come from the real estate world because there is already history of it. Developers have relationships with restaurant operators and bring them to properties but it’s not yet an accessible part of the restaurant opening ecosystem. It lives mostly in the realm of celebrity chefdom and chains. There’s value on all sides in creating a codified system for more kinds of restaurants to ‘plug in’ to real estate developments and vice versa. Developers and operators could de-risk to a degree by sharing information and forming longer term relationships. Deals could get done more quickly with less legal fees and wasted time on all sides. Perhaps larger capital partners might, over time, get more comfortable with how restaurant economics play into larger real estate developments, opening up more funding support from landlords for new restaurant projects. One thing to guard against is the likelihood that this integration would likely favor those with proven track records, making it harder for first time operators and historically marginalized groups to gain access.

Netflix vertical integration works in large part because the content is good enough, frequently enough to keep people subscribed and excited. The Doordash ghost kitchen approach is not going to yield an Orange is the New Black, Black Mirror, or Queen Charlotte. That does not mean other efforts could not. Other platform entrants looking to vertically integrate would do better to seek out the numerous local Jenji Kohans, Charlie Brookers, and Shonda Rhimes of the restaurant world who offer unique points of view and teams excited to make the food. If vertical integration led to greater access to resources for more, better restaurants it wouldn’t be a bad thing. Many would argue Netflix has helped fuel a golden age for film and television content. Turning a little local sandwich shop or Chinese restaurant into a part-time, white label production facility of mediocre, obligatory bowls is not how the next golden age of restaurants will begin. There is the potential for vertical integration to be a net positive for the industry but all stakeholder group (operators, guests, suppliers, service providers, communities, city and state governments, real estate developers) have a hand in doing it right.