I first read about the Ansonia in Dror Poleg’s Rethinking Real Estate. The building, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, was built between 1899 and 1904. William Earl Dodge Stokes was the building’s developer and envisioned it as a grand, self-sufficient apartment hotel. Stokes was a child of the wealthy Phelps Dodge mining family who left the business and developed a lot of property on the Upper West Side. The Ansonia was designed by architect Paul E.M. Duboy in the Beaux-Arts style. Among it’s claims to fame:

The 1919 Black Sox scandal was planned there

Babe Ruth and other famous Yankees called it home

At the time it was home to the world’s largest indoor pool

Bette Midler and Barry Manilow played there early in their careers

Two things struck me from a deeper dive about the Ansonia. It was wildly forward thinking in ways that feel very relevant today. The building was incredibly flexible in its uses. It was an apartment hotel, meaning guests could stay for a day or live there for decades. Thick walls meant artists and musicians could use the space for living and work. It was at the forefront of technologies at the time. A pneumatic tube system allowed guests & tenants to communicate efficiently with staff. Chilled brine in the walls was an early form of central air conditioning. Poleg says “It is no coincidence that the Ansonia sounds like a mash-up of coliving and Airbnb and brings to mind notions of the sharing economy and space-as-a-service.”

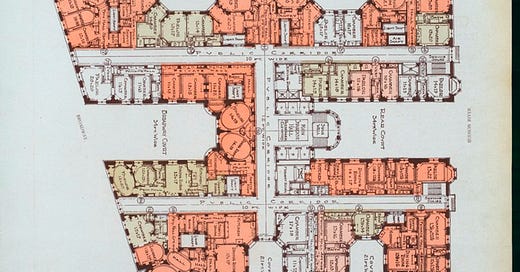

The second striking thing about the Ansonia was how integral food, beverage and hospitality were throughout the 550,000 square foot building. There was a 550 seat restaurant on the first floor, a 1300 seat restaurant on the 16th floor, and a full commercial kitchen on all floors in between. A basement shopping arcade included a butcher, bakery, milk shop, and a liquor and wine store. As part of the building's vision for self sufficiency, it included a rooftop farm with ducks, goats, and 500+ chickens. Tenants and guests received a delivery of fresh eggs daily.

Fast forward 125 years and the Ansonia is a model for residential and office real estate for today. Food uses have dominated ground floor retail in the 21st century. Rooftop restaurants have long existed to capitalize on views. The Ansonia integrated food throughout the entire building, top to bottom. The building was shaped around how urban residents, of multiple classes, lived and worked. The Ansonia also reflected how inextricable the way we live and work is from the way we eat. Take this passage from Poleg’s book where he references a quote from a French observer visiting NYC at the turn of the 20th century.

‘Americans… ate in restaurants all the time’ and ‘did no cooking at all’. In line with this lifestyle, some of the larger apartments in the building had four or five bedrooms but no kitchens. This was ideal for single residents who wanted to share a flat or for families that preferred to eat at the buildings shared dining hall (or had their servants work in a central shared kitchen instead of at home)

Our eating habits are more true today and far more people live in cities than they did in 1900.

I’ve been in 3 meetings in 2024 where the word ‘amenitize’ was used. It is actually a word; it entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 2020 as the verb form of ‘amenity’ meaning to make something more pleasant and attractive. I googled ‘JLL amenitize’ and ‘CBRE amenitize’ to see how large property management companies were leaning into the term. ‘Highly amenitized’ showed up a lot to describe both residential and office buildings. The Ansonia’s amenitization strategy began with food, and not just with the ground floor restaurant that anchors almost every building nowadays.

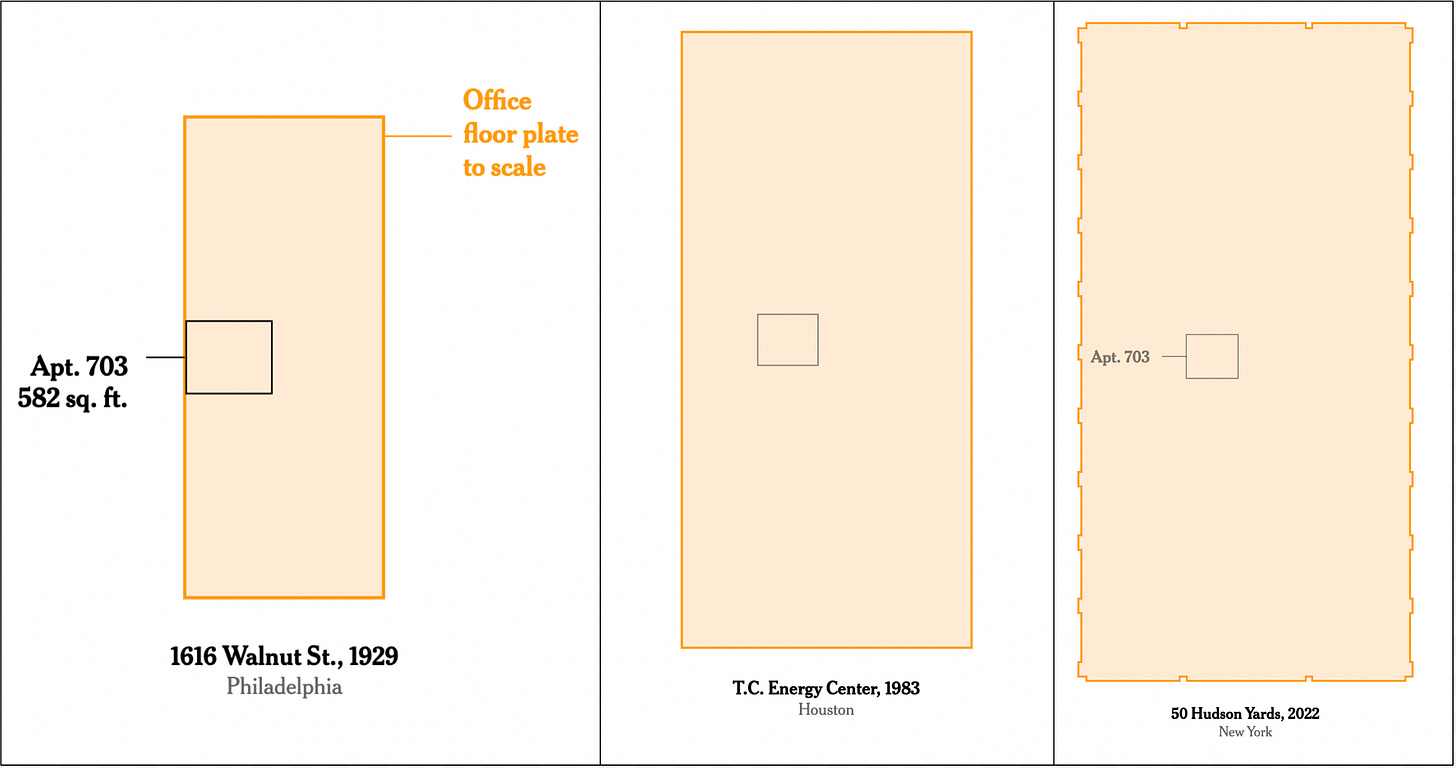

Better integrating food uses throughout a building could also help with one of the big challenges of converting modern office buildings into residential. Most office buildings were built before 1940 or after 1970. Those built earlier have smaller floor plate sizes that make sense for residential conversion. Those built later, what we think of as a modern office building tower, have huge floor plates. A recent NY Times interactive piece covers this really well, but to simplify, older office buildings needed access to open windows for cooling and natural light so no part of the building was more than 25-30 feet from a window. This distance is in line with what one would want for residential living. In newer office buildings, with access to air conditioning and better lighting that distance didn’t matter as much. So you end up with big open floors where, once you carve it up, there’s too many interior, windowless spaces. Now imagine taking a page from the Ansonia playbook and creating shared infrastructure around the interior spaces. This could be bookable kitchens, event spaces and other amenities.

It makes sense to look to the turn of the 20th century for ideas to address the challenges of 2024. The last 25 years of the 1800’s were deemed the Gilded Age and many believe we’re living through the Second Gilded Age now. Both periods are/were defined by rapid technological advancement, economic inequality, consolidated corporate power, and increased social and labor movements.

But the Ansonia was not exclusively for the rich. Smaller apartments were reasonably affordable, accessible to teachers, artists, and young professionals. The building leveraged the extremely contemporary concepts of co-living and shared spaces along with lavish amenities to create housing that worked across classes. Fun fact, the term Gilded Age and the quote ‘history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes’ are both attributed to Mark Twain.

The centralization and broad integration of food in real estate development is already happening. Early entrants are at the extreme high end. Major Food Group, of Carbone fame, is developing The Villa in Miami under their own brand. The Millenium Winthrop Center in Boston tapped Chef John Fraser for 5+ food operations in the $1B building. While both of these represent the ultimate ‘Second Gilded Age’ properties, they’re still instructive.

Food partners must be brought in at the inception of a project to inform building layout and design from a hospitality and food-service perspective. Concepts must be developed in concert to account for all the ways people eat: across meal periods, a mixture of price points, vice & virtue, on & off premise offerings, and even varying degrees of meal preparation. Early involvement will lead to deeper relationships between developers, property managers, and restaurant operators. Every element of foodservice operations will be coordinated for economies of scale and optimization. Restaurant tech partners will facilitate ordering and communication throughout buildings. Eventually, gig work platforms might connect workers with shared amenities within the buildings. It gets pretty Downton Abbey, Upstairs/Downstairs but it’s not hard to see a world where lower floors offer affordable housing (often required by cities in new development) where some residents work within amenities on higher floors.

If this sounds like a mix of hotel/cruise ship/apartment/condo building, it is. If it sounds vaguely like the dystopian sci-fi of Ready Player One, Elysium, or Bladerunner, it could be…but doesn’t have to be. Cities will continue to densify, office space will need to be reimagined and highly adaptable, and we’ll always need to eat. The Ansonia’s relevance in the 21st century underscores a fundamental truth: spaces that adapt to our evolving lifestyles, particularly in how we approach food and community, are not just desirable but essential. As we navigate the complexities of modern city life, the Ansonia's focus on flexibility along with centering food, beverage, and hospitality throughout the building offer a blueprint for creating spaces that resonate with our times and beyond.